The Theory of Colour

The basis of this article will be discussing the twisting questions:

"What is the True Colour of Something?? and "Do All People See the Same Colour?"

Before we discuss colour, we must have an understanding of how the eye works and how we perceive colour.

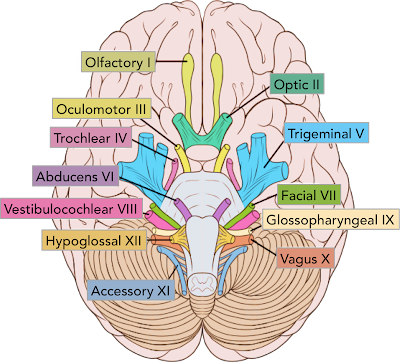

To see something, a wave of light emitted from a source is reflected off of the desired object and enters our eye, through the cornea (transparent layer protecting the eye), through the pupil and it is refracted by the lens so that the light rays converge (meet) at the retina. The information from the light rays are then converted into electrical signals/nerve impulses which are carried to the brain via the optic nerve.

The retina is packed with photo receptors, which detect light as a stimulus for the creation of a nerve impulse. These are called rods and cones.

The cones are the cells responsible for daylight vision and respond to colour wavelengths of red, green and blue. The human eye only has about 6 million cones. Many of these are packed into the fovea centralis, a small pit in the back of the eye that only measures about 0.3mm wide.

The rods work best at low levels of light, and are used for night vision. They are sensitive to light, but not the wavelengths of different colours. Humans have over 100 million rod cells which have come about via evolution. This is why at night, we see everything in gray-scale.

Whats quite interesting is that in dim light, you can see more clearly out of the side of your eye, because the rods are more concentrated at the sides of the eye.

So how do our cones know which colour is which? When light hits an object, we know it reflects. But only specific wavelengths of the light are reflected, the rest being absorbed.

Not all cones are the same however, for example, most cones are actually attuned to be more sensitive to red light (since in the visible light spectrum, the wavelength of red is the longest at 625-740nm, the light of red colour is scattered least by the air molecules of the atmosphere and therefore a light of red colour can penetrate to a longer distance. Perhaps it is due to evolution that most of our cones are this way, as red is also the colour of blood and signifies danger [also this is why red is used for construction and road signs].)

This post shows us that most variants of modern bird actually have four cone cell variants (tetrachromacy) compared to us humans who only have three. So they can actually see ultraviolet light, or light shorter than ones in the visible light spectrum.

Not only in birds, but many insects as well such as bees:

I think that theoretically, no one really knows the actual colour of something, it would be relative to a species. No species can see every wavelength of every colour there is, therefore no one in the universe knows exactly what colour something is?

"Even if two people have perfectly functioning color vision, does each person experience the same color when they both look at an orange together? Obviously, both will answer in the affirmative if asked if the fruit is orange. But that's just a word, and if one grew up with a brain that transformed everything orange into the experience of blue, and vice-versa, there might never be a way to say for sure if you and your friend aren't as similar as you think."

Further Reading // Sources

https://curiosity.com/topics/do-you-see-the-same-colors-as-everyone-else-curiosity

https://www.livescience.com/32559-why-do-we-see-in-color.html

https://www.sightsavers.org/protecting-sight/the-eyes/

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/53f7/40595af0ba41213cd4ddd4bc7e14b2251c45.pdf

https://www.quora.com/What-true-colour-is-an-object

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetrachromacy

To see something, a wave of light emitted from a source is reflected off of the desired object and enters our eye, through the cornea (transparent layer protecting the eye), through the pupil and it is refracted by the lens so that the light rays converge (meet) at the retina. The information from the light rays are then converted into electrical signals/nerve impulses which are carried to the brain via the optic nerve.

The retina is packed with photo receptors, which detect light as a stimulus for the creation of a nerve impulse. These are called rods and cones.

The cones are the cells responsible for daylight vision and respond to colour wavelengths of red, green and blue. The human eye only has about 6 million cones. Many of these are packed into the fovea centralis, a small pit in the back of the eye that only measures about 0.3mm wide.

The rods work best at low levels of light, and are used for night vision. They are sensitive to light, but not the wavelengths of different colours. Humans have over 100 million rod cells which have come about via evolution. This is why at night, we see everything in gray-scale.

Whats quite interesting is that in dim light, you can see more clearly out of the side of your eye, because the rods are more concentrated at the sides of the eye.

So how do our cones know which colour is which? When light hits an object, we know it reflects. But only specific wavelengths of the light are reflected, the rest being absorbed.

Not all cones are the same however, for example, most cones are actually attuned to be more sensitive to red light (since in the visible light spectrum, the wavelength of red is the longest at 625-740nm, the light of red colour is scattered least by the air molecules of the atmosphere and therefore a light of red colour can penetrate to a longer distance. Perhaps it is due to evolution that most of our cones are this way, as red is also the colour of blood and signifies danger [also this is why red is used for construction and road signs].)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To answer the first question very bluntly: we don't know. You may think that a banana is yellow, but that is because every human agrees that it is yellow (or their idea of yellow [second question]), but as a matter of fact there are other species which have a visionary system much more complex than ours. |

| J E N C H R I S T I A N S E N ; S O U R C E : T I M O T H Y H . G O L D S M I T H |

Not only in birds, but many insects as well such as bees:

I think that theoretically, no one really knows the actual colour of something, it would be relative to a species. No species can see every wavelength of every colour there is, therefore no one in the universe knows exactly what colour something is?

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

With the exception of those who are colourblind (stats come in at 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women), there is another theory that everyone has a different perception of colour."Even if two people have perfectly functioning color vision, does each person experience the same color when they both look at an orange together? Obviously, both will answer in the affirmative if asked if the fruit is orange. But that's just a word, and if one grew up with a brain that transformed everything orange into the experience of blue, and vice-versa, there might never be a way to say for sure if you and your friend aren't as similar as you think."

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Further Reading // Sources

https://curiosity.com/topics/do-you-see-the-same-colors-as-everyone-else-curiosity

https://www.livescience.com/32559-why-do-we-see-in-color.html

https://www.sightsavers.org/protecting-sight/the-eyes/

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/53f7/40595af0ba41213cd4ddd4bc7e14b2251c45.pdf

https://www.quora.com/What-true-colour-is-an-object

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetrachromacy

Comments

Post a Comment